Today, alcohol consumption in Russia remains the highest in the world. The high volumes of alcohol consumption have resulted in serious consequences socially, politically and economically. The public health ramifications have been an ever going issue throughout the years and has led to alcoholism to be thought of as a ‘national disaster’. In the 1970’s, alcoholism had been linked to high rates of child abuse, suicide, divorce and a rise of mortality rates, especially among males. It was estimated the two-thirds of murders and violent crimes were committed by intoxicated individuals in 1980 and the death toll from drunk drivers was on an incline. The problem ultimately stemmed from the idea that drinking was seen as a pervasive, socially acceptable behavior in society.¹ Consumption of alcohol holds deep cultural roots in Russia, it often accompanied an array of celebrations, indicated hospitality and created bonds between individuals. It was a source of revenue for the Soviet state, which created tremendous income and was exercised as a monopoly on it’s production and distribution.¹ With the negative ramifications growing and society being impacted as a whole, Mikhail Gorbachev thought he had the solution.

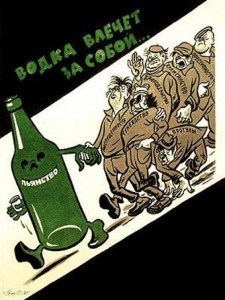

A classic poster from a previous anti-alcohol campaign

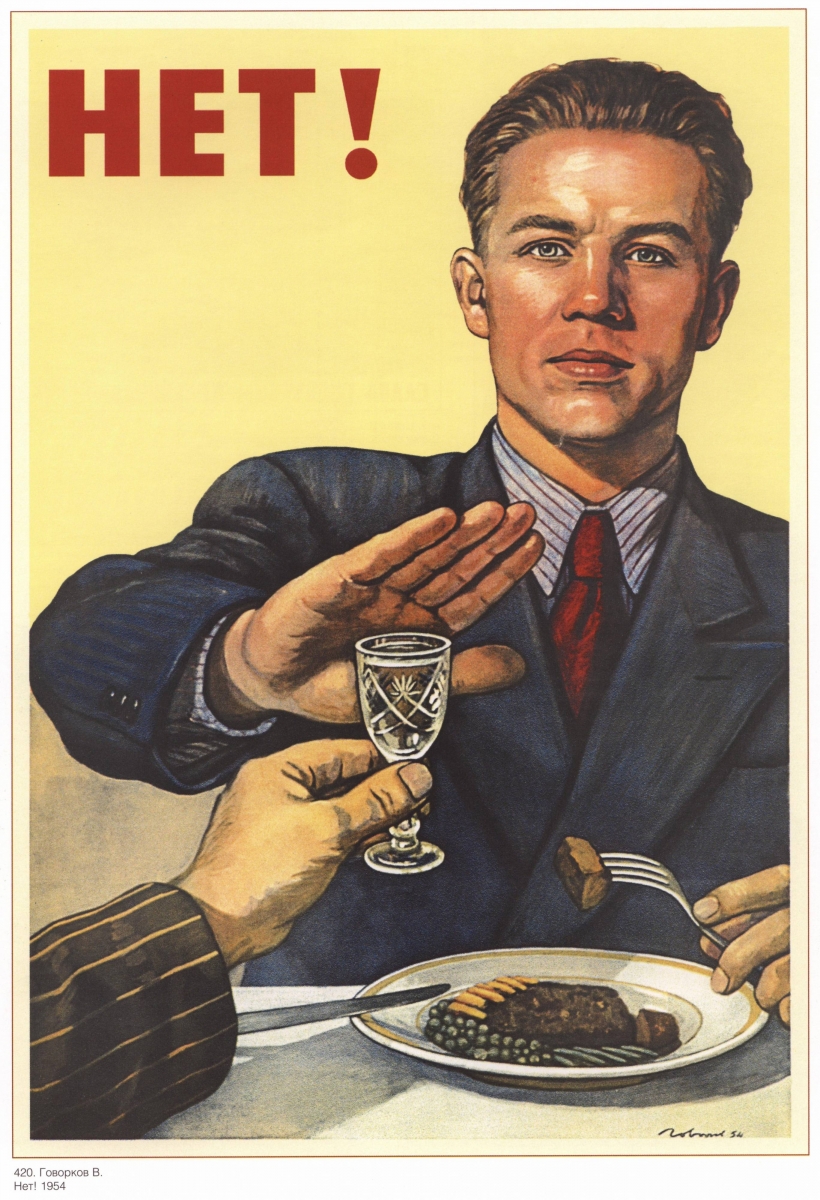

Mikhail Gorbachev was not only known as the General Secretary but became known as the ‘mineral’nyi sekretar’ (mineral-water-drinking secretary).¹ In May of 1985, less than two months after becoming General Secretary of the Communist Party, Gorbachev launched a campaign against alcohol abuse. It introduced ‘partial prohibition’, the prices of vodka, wine and beer were increased and their sales were restricted to certain times of the day.² It also included limiting the kinds of shops that were permitted to sell alcohol which resulted in the closings of distilleries and vineyards. Even official Soviet receptions became alcohol-free events. Ultimately, the campaign had an effect on alcoholism country wide. It improved quality of life measures however it was very unpopular among the population.

Economically it was detrimental to the state budget since the alcohol production migrated to the black market. It also contributed to the sharp increase in the production of moonshine and the use of more dangerous substances.² The decline in state revenue created a major budgetary imbalance that led to printing more money which fueled inflation.¹ Eventually all these reasons led to the campaign being abandoned after 1987 and the legal use of alcohol being reintroduced.

¹ “Anti-Alcohol Campaign.” Seventeen Moments in Soviet History, 2 Sept. 2015, soviethistory.msu.edu/1985-2/anti-alcohol-campaign/.

² Vasinsky, A. “WHO PERMITTED THE PROHIBITION?-POLEMICAL REFLECTIONS ON THE FORBIDDANCE COMPLEX.” EVXpress – WHO PERMITTED THE PROHIBITION?-POLEMICAL REFLECTIONS ON THE FORBIDDANCE COMPLEX – Current Digest of the Russian Press, The , 1987 , No. 52, Vol. 38, dlib.eastview.com/browse/doc/19994679.

Cover photo: Anti-Alcohol Campaign Poster “Socially Harmful”